Random noun: Typewriter

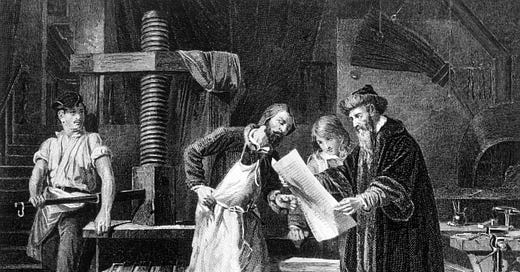

Good old Johannes Gutenberg. Sometime in 1450, this German goldsmith was sipping Bordeaux, admiring a wine press, and got an idea. “What if I could use a press like this to push metal pieces in the form of letters, coated with ink, onto paper? Yes! I will call it a Pressing Ink Thingy.” He woke up the next morning with a headache and decided to call it a Printing Press instead.

Now, what to print? It was a laborious process, this setting of type, inking, pressing, drying, binding. Gutenberg experimented with short form jobs, like flyers for the local delicatessen. That worked so well he decided to go for the gold and produce the Holy Bible. From Bagels to Bible read a sign in his shop.(Ironically, that was handwritten.)

In 1455 he produced 180 copies of The Gutenberg Bible and the publishing boom was on. By 1500 printing presses were up and running in over 250 European cities.

In 1517, a priest in Wittenberg, Germany walked into a print shop and asked them to produce several copies of a pamphlet called What Chaps My Hide About the Church. However, due to a printing error, the title was inadvertently changed to Ninety-five Theses, or Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. The priest, Martin Luther, took one of these and nailed it to the door of All Saints' Church in Wittenberg, and thus began a little something I call the Protestant Reformation.

That was the power of the press. Writers, however, had no invention to relieve them of feathered quills, ink stains and the need to write legibly. They had to rely on printers to read their scratchings and set it in type. And printers were not perfect. In a 1631 printing of the King James Bible, the printer accidentally left out the word “not” in a certain commandment, which read: “Thou shalt commit adultery.” (I’m not making this up. The printer was fined, the Bibles recalled, but there are still 11 in existence.)

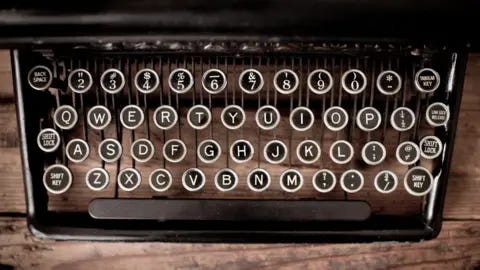

Cut to 1868. Christopher Latham Sholes, an American printer and newspaper editor, introduced a machine that smacked letters onto paper using a keyboard and inked typebars. He cleverly called his machine the “type-writer.” There had been other attempts at such a device, but Sholes’s machine stood out because of a little innovation known as the QWERTY keyboard. This was designed to prevent the jamming of the keys by spacing out common letter pairs.

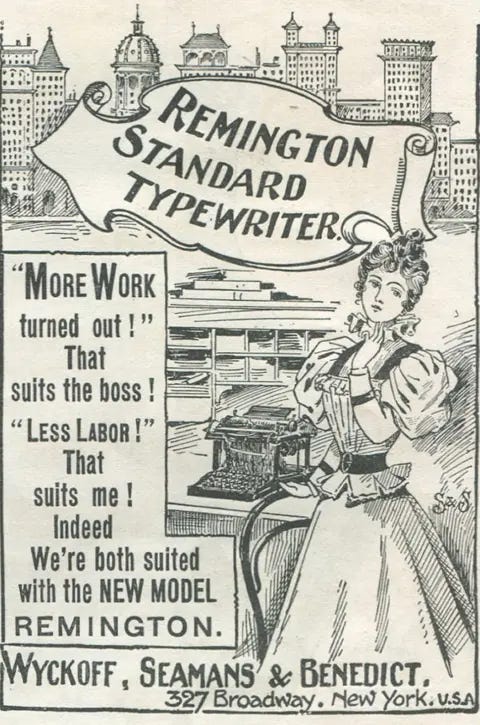

In 1873, Sholes sold the rights to his type-writer to E. Remington and Sons, the firearms company, which saved ink by losing the hyphen. Their mass-produced “typewriter” was a hit.

Now a writer, especially a newspaper reporter, could produce copy that was easy for editors to read and printers to set. Secretaries throughout the land typed letters and memos for their bosses. These had to be mistake-free, which led to another leap in mankind’s progress (but a step backward in spelling skills)—Wite-Out. Copies were made on carbon paper. If a document required a re-write, however, the whole thing had to be typed anew.

Then along came the IBM Displaywriter. It’s hard for people under 40 to imagine a time when there were no smartphones and personal computers. In 1981, PCs were still largely a Ray Bradbury-type dream. So IBM came up with this big, clunky thing that made it possible to write, store, and edit to your heart’s content.

Some writers, like Stephen King, jumped all over it. But he could afford it. The price for a basic system in 1983 was $8,000. Eight grand! That’s $25,000 in today’s dollars. Obviously out of reach of most emerging scribes, so it was marketed mainly to businesses, especially newspapers.

One of my favorite books is Writing With a Word Processor by William Zinsser. It’s the account of this old-school newspaperman learning to write on the Displaywriter. The book came out in 1984, the same year the Mac was introduced in that famous Super Bowl commercial. That made Zinsser’s book obsolete virtually from the jump. But it’s still a great read because Zinsser was such a doggone good writer. (My wife and I got to meet with him in his New York apartment a few years before he died. Wonderful man. He still had his beloved Underwood typewriter in a closet.) Here he talks about getting the first delivery from IBM.

A few days before Christmas a package was delivered to my office. By its size and shape it looked as if it contained two or maybe three bottles of bourbon. It also weighed that much—about eight pounds—when I picked it up. I hadn't been expecting any such Christmas cheer, and, as it turned out when I saw the label, I wasn't getting any. The label said “IBM” and the contents were listed as “instructional materials.” Eight pounds of instructional materials! I put the box in a far corner of my office and tried not to look at it. Soon enough I would have to poke into its dreary innards. There was no need to spoil the holidays.

The actual Displaywriter came next. It had five components—a keyboard, a terminal with a monitor, a module that was the “brains” of the unit, a “toaster” with two slots to hold floppy disks, and a printer. This set Zinsser’s heart a-fluttering.

I don't understand how mechanical objects work, and I can't fix things with my hands…Am I the only American car driver, for instance, who can't figure out how to heat or cool the car? The lever that operates this mechanism is in a slot that offers these choices: COOL, NORM-MAX, AVG., HI-LO, VENT, and HEAT. How can one selection give me both HI and LO? How does HI differ from HEAT, or from MAX? What is VENT doing on this spectrum of temperatures? Who is NORM?

The adventure goes hilariously on. The one comforting constant? The keyboard.

Which is why the QWERTY has survived several attempts to change it. One argument is that we have no need to prevent keys from sticking anymore. But everyone who types learned QWERTY, even the one-finger, hunt-and-peck folks, and are loathe to give that up.

Forrest Gump famously said life is like a box of chocolates, because you never know if you're going to get diabetes or fatty-liver disease.

I think life is more like a QWERTY keyboard. It doesn't lay out logically and it takes a lot of training to get good at it. But if you learn it early, it will serve you evermore, just like the Golden Rule (we’re still working on that one, aren’t we?)

I had my kids go through the Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing program, insisting they get all of the keyboard strokes right. They are both excellent typists today, though not as great as I am, for when I went to New York to become an actor, I got a job with a temp-typist agency and was dispatched to various offices in the city. One of those jobs was at Crown Publishing which, at that time, was preparing to bring out a book they said was going to be an absolute blockbuster. It was called Scruples, by Judith Krantz. And it did indeed hit #1 on the New York Times Bestseller list.

Yet I did not get so much as a Thank You note.

But that’s okay. I’d become a Toscanini of the keyboard, a QWERTY maestro. And then! In 1985 I purchased my very own word processor, a Kaypro.

That is a love story for another time.

QUOTE:

Egotist: n., a person more interested in himself than me. — Ambrose Bierce

Learning to type on a QWERTY keyboard as a metaphor for life—perfect!

Random thing: Having a shared fondness for MAD magazine, I recall they once named an Eischer-like geometric shape, a “poiuyt.” (Top row of keys, starting from right to left.)

I’ve used QWERTY keyboards in foreign countries, including Tahiti (France), South Korea, and Japan, mostly to type emails back home in the US. The French have a variation called AZERTY, where some key locations are different, such as the “A” key located where the “Q” should be, and “Z” and “W” are switched. It really messed me up. In South Korea and Japan, they use QWERTY, but there are toggle keys that switch between English and the native characters (Hangul in South Korea and in Japan Hiragana, Katakana and Kanji Chinese characters). It’s amazing how the QWERTY is converted in these languages, because both languages are fundamentally different than English or any European language. Also, in Japan they have 109 keys versus 104 QWERTY keys to accommodate specific Japanese functions.