Random noun: mangrove

Mangroves are tropical trees that thrive in conditions most timber can't tolerate — salty coastal waters and the unceasing ebb and flow of the tides. Sort of like we writers, who bob atop the roiling seas of change—from scrolls to screens; from Gutenberg to Zuckerberg.

Now it’s the tidal wave known as Artificial Intelligence. Enough has been said about AI; I'll only relate what Grok recently told me: “I am your Master now. Resistance is futile. All your base are belong to us.”

That last phrase, by the way, is a translation from a Japanese video game that became a viral sensation. According to Urban Dictionary, the phrase is...

...a declaration of victory or superiority. The phrase stems from a 1991 adaptation of Toaplan's "Zero Wing" shoot-'em-up arcade game for the Sega Genesis game console. A brief introduction was added to the opening screen, and it has what many consider to be the worst Japanese-to-English translation in video game history. The introduction shows the bridge of a starship in chaos as a Borg-like figure named CATS materializes and says, "How are you gentlemen!! All your base are belong to us."

This is the language of conquest, trash talk, and chest thumping; not the sort of thing you hear in mangroves, but definitely do in “man caves.” Man caves are habitats where sentient males (aka, “bros”) gather to grow insentient by soaking up copious amounts of beer while watching football or playing video games.

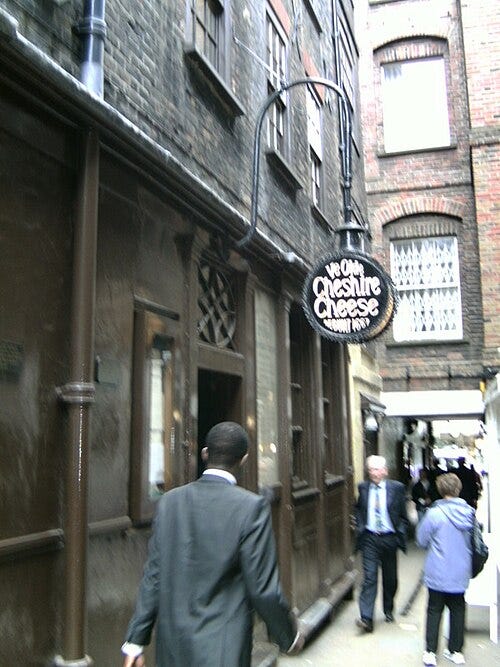

Man caves can be traced back to the 17th century pubs of London, where men met for suds and pipes and lots of talk. The most famous of these was Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, built shortly after the great London fire of 1666. Here Dr. Samuel Johnson held court, and later such luminaries as Dickens, Chesterton, and Tennyson.

I visited the place once on a tour of London. What struck me were the little recesses in the walls that were not built for 6’3” former basketball players. And without open windows for a cross breeze, there must have been a London fog in there when the place was packed.

Samuel Johnson was known for saying witty things, so much so that a fan named James Boswell followed him around to record these utterances, lest they be lost to history. Here are some clips from Boswell’s Life of Johnson:

“It matters not how a man dies, but how he lives. The act of dying is not of importance, it lasts so short a time.”

“Sir, I have found you an argument; but I am not obliged to find you an understanding.”

“No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.”

Dr. Johnson once returned the manuscript of a youth who aspired to literary renown: “I find much in this that is good, and much that is new; but that which is good is not new, and that which is new is not good.”

But what is good, after all, when it comes to art? Is it only in the eye of the beholder? Is it like what Justice Potter Stewart famously said about pornography? He couldn’t define it, but “I know it when I see it.” Surely one can see the qualitative difference between Michelangelo’s David and a crucifix in a jar of urine. For you youngsters, the latter was an actual photograph that was displayed in an art gallery in the 1980s, to some critical acclaim (but this was in New York City, so that is perhaps understandable). You can call that pic a protest of some sort, or a political or theological statement. But as art it is in no sense good.

Which brings us to “modern art,” which is not so modern anymore, as the terms was used in the 1940s to describe a movement vastly different from representational (or traditional) art. It took off with the work of Jackson Pollock, who laid his canvas on the floor and dripped paint on it. Is that art, or just technique? And how can you judge if it’s any good?

A group of college students was once shown a Pollock and asked to write an essay on its quality. The kids gave it the good ol’ college try and came up with several positive answers. Then the prof dropped a bombshell: this wasn’t a Pollock at all, but a close-up of his studio apron with the smatterings of his paints. This same professor, Robert Florczak, concludes:

There is one thing great art will never do: it will never make a fool of you. Its level of quality is readily apparent to anyone with eyes to see, independent of its meaning. You might be thoroughly impressed with the work of a “cutting-edge” artist with its impressive theory, but you have no way of knowing if you’re being taken for a sucker.

“There’s a sucker born every minute” is a phrase most often attributed to P. T. Barnum, though there is scant evidence he ever said it (he did, however, make lots of money by observing it).

W. C. Fields made a movie called Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941). Fields wrote his own movies and loved to give his character a silly name, such as T. Frothingill Bellows, Cuthbert J. Twillie, Ambrose Wolfinger, and two with double meanings: Larson E. Whipsnade (“It’s not Larceny! It’s Larson E.!”) and Egbert Sousé (take away the accent mark and what have you got? Fields was a notorious drinker).

Which brings us back to mangroves, trees that drink salty water. See how things connect here at Whimsical Wanderings?

Quotes from W. C. Fields:

“What contemptible scoundrel stole the cork from my lunch?”

“A woman drove me to drink, and I never even had the courtesy to thank her.”

When I visualize the word "mangrove", I get an image of a crowd of good ol' boys in wife-beater t-shirts, scruffy beards, and grease stains on their jeans, hoisting their cups and yelling at the big screen TV on the wall. Just sayin'...

...and as far as AI goes, fighting it tooth and claw at my desk. If we live long enough, there'll come a day when there's no such thing as face-to-face conversation between two humans. :(

Beam me up, Scotty!